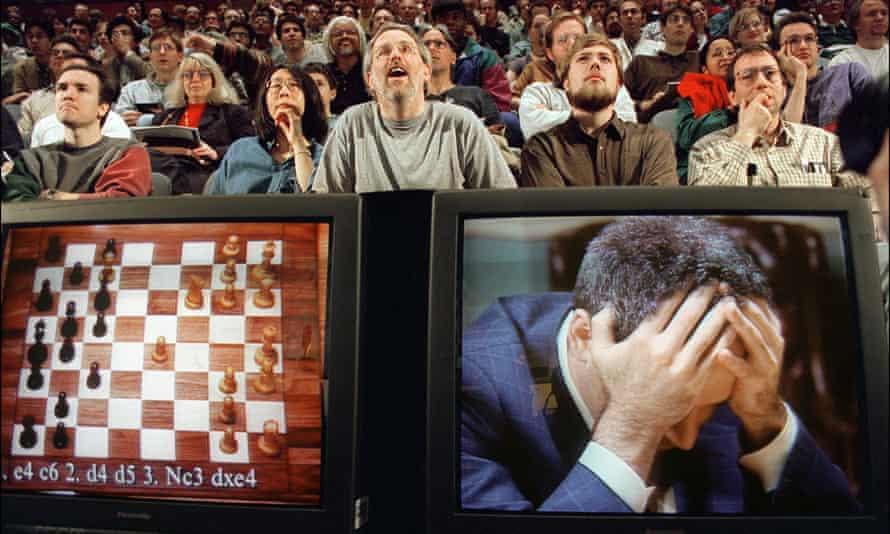

Artificial Intelligence has proven time and time again that it can, not only assist, but replace the human mind, and it just keeps getting more and more sophisticated. AI can write books, diagnose and treat diseases, drive cars, unravel stories hidden within documents, and be a grandmaster at chess, to name a few.

If AI is capable of such advanced achievements, is it so hard to believe that it is capable of creating a patentable invention? An AI’s capability isn’t the main question though. The main question is: should we allow AI to be recognized and listed as an inventor that’s worthy of merit and patent ownership?

This patent application stirred up extensive discussions in patent offices in the US, Europe, Australia, and South Africa. Since then, much deliberation has resulted in dismissals in courts across the US, EU, and UK. The main stumbling block was not that the examiners couldn’t believe that a machine could invent something, it was that they couldn’t see how a machine can own the invention. Ownership is an extremely important element the patent process.

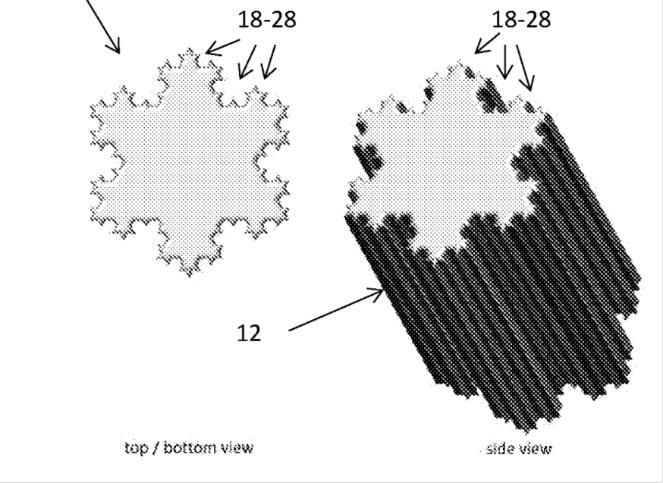

In further detail, DABUS is an AI system that simulates human brainstorming and creates new inventions. DABUS is a specific type of AI that can be thought of as creativity machines for their capability in independent and complex functioning. This is different from the AI in our everyday life, such as Siri, which is programmed to retrieve information from a database rather than “create” its own original information.

Dr. Thaler, a pioneer in machine learning inventions, has created many kinds of creativity machines. Before DABUS, he built an AI which invented a cross-bristle toothbrush design. He filed a patent for the cross-bristle design, it met the standards for patent approval, and a patent was ultimately granted. This has proven that AI does indeed have the ability to create truly original inventions that meet patent procedures. At the time, Dr. Thaler listed himself rather than the AI as the inventor for the toothbrush, so it was approved without the whole AI debate.

This time, Dr. Thaler decided instead to list DABUS as the rightful inventor of the food container, as the invention was fully conjured by the AI. He said DABUS independently designed a fractal-shaped container for improved grip and heat transfer, and an emergency beacon that flashes more noticeably. So, he cannot take credit as the actual inventor.

DABUS became the start of their push for AI to be recognised as inventors everywhere in the world. South Africa’s government said yes because it wants to increase innovation to solve the country’s socio-economic issues, which is necessary to really capitalise on the fourth industrial revolution: Artificial Intelligence.

Much to the surprise of the global community, South Africa became the world’s first to grant a patent to an Artificial Intelligence system. In 2021, South Africa’s patent office recognized DABUS as an inventor, but has not yet explained its reasons for deciding so.

This ground-breaking decision received backlash from intellectual property experts everywhere, labelling it as a mistake, an oversight, or an incorrect decision in law. IP experts argue an AI lacks the necessary legal rights to qualify as an inventor. Critics even go as far as questioning South Africa’s IP procedures and standards, that if they had a substantive search and examination system in place, the DABUS patent application would have been rejected.

Australia’s Federal Court also ruled an artificial intelligence system can be named as an inventor, explaining that we cannot restrict a narrow view on the concept of ‘inventor’ because that would inhibit innovation. If ownership is the issue, it can be resolved with granting a ‘title’ to the applicant, the same way a farmer receives the title for the milk his cows produce.

There are concerns that accepting machines as inventors could create an avalanche of automated patent generators, the same way AI has been used in content farms and spambots. This would be advantageous to dominant tech companies for whom AI is central, such as Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Alibaba. These platforms have a huge pioneer advantage in AI, easily allowing them to turn into monopolists and gatekeepers. That sounds really scary to aspiring inventors and small businesses.

However, that fear is largely disproportionate to reality.

Firstly, to get a patent, an invention must satisfy a list of stringent, lengthy, legal requirements. Applicants must prove the invention has ‘worldwide novelty’ and involves an inventive step. Secondly, patents are expensive, plus there are maintenance fees too. This is a big disincentive to abuse the patents system. Thirdly, patent owners have to abide anti-monopoly laws, so action can be taken against those seeking to abuse IP rights to stifle competition.

Some have expressed concerns that, by accepting AI as inventors, it would elevate the status of AI to a legal person. Others have also suggested that if we allow AI-generated inventions to gain patent protection, it would give an unfair advantage to human invention, which undoubtedly cannot match the processing capacity of a computer. This will make it harder for human inventors to secure patent rights.

Justice Beach of the Australian Federal Court – the person who allowed AI to be named as an inventor – said that whether the inventive step is produced by a human or a machine is irrelevant and is not at all concerned with the inventor’s mental processes or characteristics whatsoever. Instead, the focus is on comparing the new idea to the field’s prior base and common general knowledge, and encouraging new knowledge to be invente

Let’s say we ignore all these issues and decide that AI cannot be named as an inventor, then that would mean the patent is invalid, since the alleged invention has not in fact been made by the nominated human, but by AI.

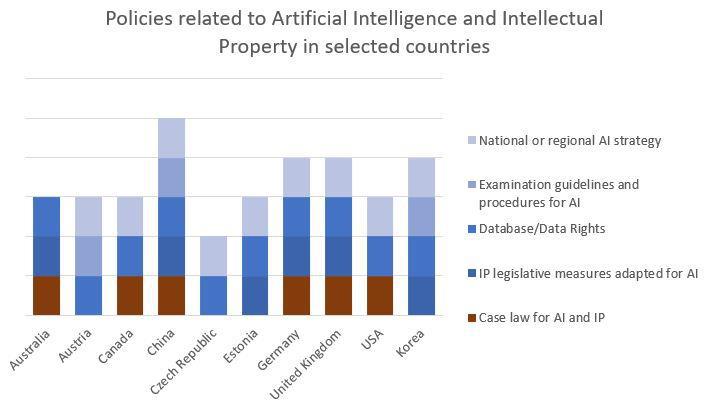

The depth of this discussion varies in different countries.

Right now, AI is literally challenging the essence of innovation. Clearly, AI highlighted existential questions about the core principles of the patent system including ownership, inventorship, and infringement that has to be discussed and solved. Other debates surrounding Artificial Intelligence in Intellectual Property matters are unavoidable as well, with AI being more and more heavily utilised.

Today countries need to unambiguously state at least what AI can and cannot do. Patents officials have to also sort out how they will interpret the existing rules to fit the moral, ethical, and legal facets of AI inventions, where caution is prudent.